Unveiling the Grand Canyons of the Moon

Two Immense Canyons Discovered on the Far Side of the Moon

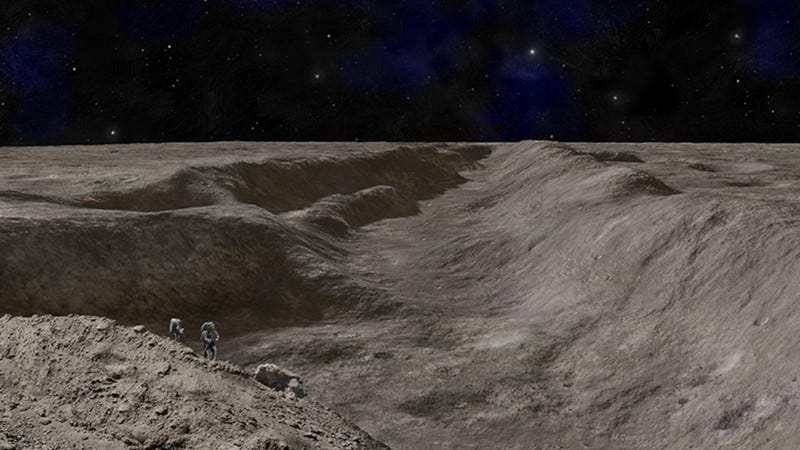

In a significant discovery, a team of scientists at the Lunar and Planetary Institute (LPI), an institute of the Universities Space Research Association (USRA), found that two immense canyons hidden in the lunar f…