NASA Reauthorization Bill Aims to Lock In Commercial Role in Space Economy

Scheduled for Markup in the House Science, Space and Technology Committee Wednesday

A new NASA authorization bill in the U.S. House of Representatives would deepen the agency’s reliance on U.S. commercial space companies for everything from lunar landers and spacesuits to space station cargo flights and future commercial stations in low-Earth orbit, potentially steering billions of dollars in work toward the private sector over the next decade.

Lawmakers will hold their first discussion of the bill Wednesday in a hearing called a “Markup” in the House Science, Space and Technology Committee.

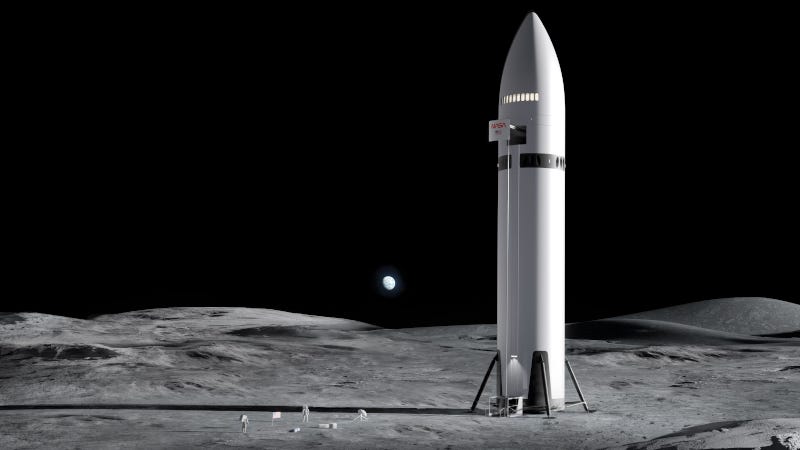

The NASA Reauthorization Act of 2026 explicitly empowers the NASA Administrator to enter into agreements and public–private partnerships with U.S. commercial providers to support human exploration of the Moon and cislunar space, expanding a model pioneered for cargo and crew to the International Space Station (ISS). The bill directs NASA to “support the development and demonstration of” human-rated lunar landing capabilities and, subject to funding, to procure those capabilities from “not fewer than two commercial providers,” effectively guaranteeing a multi‑vendor market for lunar landers and related services.

The legislation requires that any commercial provider supplying human lunar landing systems be a U.S. commercial provider, reinforcing a domestic industrial base for high‑end human‑spaceflight hardware and operations. By tying these systems directly to NASA’s Moon‑to‑Mars roadmap and Artemis missions, the bill signals steady demand for lunar transportation and surface operations that could anchor long‑term business plans in the commercial space sector.

Commercial Low‑Earth Orbit Platforms and ISS Transition

The bill positions commercial space stations and other private platforms as the backbone of U.S. low‑Earth orbit operations once the ISS is retired, directing NASA to spell out its research, development, and operational requirements in orbit and share them with U.S. industry. NASA must provide an accounting of these needs—including factors that could affect design, instrumentation, and long‑term operations of “future United States commercial low-Earth orbit platforms and supporting capabilities”—within 90 days of enactment.

Another section orders a report on the risks of any gap in U.S. access to low‑Earth orbit platforms, including the potential impact on “the development of the United States-based commercial space industry,” and explicitly lists “increasing investment in and accelerating development of commercial space stations” as one option to prevent such a gap. By writing commercial platforms into the strategy for replacing the ISS, the bill effectively treats private space stations as critical national infrastructure and a central pillar of the future orbital economy.

Expanded Commercial Roles in ISS Operations

In the near term, the measure would sustain existing commercial markets tied to the ISS and open up additional lines of business. It instructs NASA, subject to appropriations, to maintain a flight cadence of crew and cargo missions on U.S. commercial vehicles at no less than the average of the previous three years, locking in a steady stream of contracts for commercial crew and cargo providers for as long as the station operates.

The bill also formally authorizes NASA to enter into agreements enabling U.S. commercial companies to conduct nongovernmental human missions to the ISS under NASA policies and federal regulations, recognizing privately funded astronaut flights as a component of the evolving low‑Earth orbit economy. A mandated review by the Government Accountability Office will examine how many such missions are flown, whether companies fully reimburse NASA’s associated costs, and how those flights affect NASA’s own science and technology priorities, potentially shaping future pricing and access policies for commercial ISS use.

Spacesuits and Other Critical Systems as Commercial Opportunities

NASA is directed to “obtain advanced spacesuit capabilities” for exploration, but the bill also requires that any commercial provider delivering those capabilities be a U.S. company, placing next‑generation extravehicular activity systems squarely within the domestic commercial market. NASA must maintain core in‑house expertise and keep Johnson Space Center in charge of spacesuit and EVA programs, but is explicitly tasked with doing so “including through partnerships with the private sector,” reinforcing a hybrid government–industry development model.

The Act further calls for detailed reporting on government and private investment in commercial human lunar lander contracts, including milestone payments, cost and schedule challenges, and steps being taken jointly by NASA and providers to overcome those challenges and keep Artemis on track. That level of transparency could shape investor confidence in major commercial human‑spaceflight programs and influence how future fixed‑price or milestone‑based contracts are structured across the industry.

Guardrails and Strategic Signals for Industry

While the bill aims to expand commercial roles, it also tightens guardrails by requiring NASA to certify compliance with existing “commercial item” and competition statutes for major agreements, and by mandating reports on alternative approaches if commercial providers cannot meet cost, schedule, or performance targets for human lunar landings. That combination of opportunity and oversight signals that Congress expects the commercial space sector not only to innovate, but also to deliver reliably on missions central to U.S. space leadership.

Collectively, the provisions would entrench commercial companies as indispensable partners in NASA’s exploration, ISS transition, and low‑Earth orbit strategies, creating long‑term demand for launch, in‑space transportation, station operations, spacesuits, and other services while subjecting the largest programs to new layers of scrutiny.

Solid reporting on the bill language. The part about treating private space stationsas critical national infrastructure feels like a big shift in how Congress views commercialproviders, not just suppliers but key operators. I'm curious if the GAO review mechanism will actaully refine pricing models or just become another paperwork layer tho.