BepiColombo Swings by Mercury for the 6th Time

Closest Approach Came at 0200 EDT This Morning

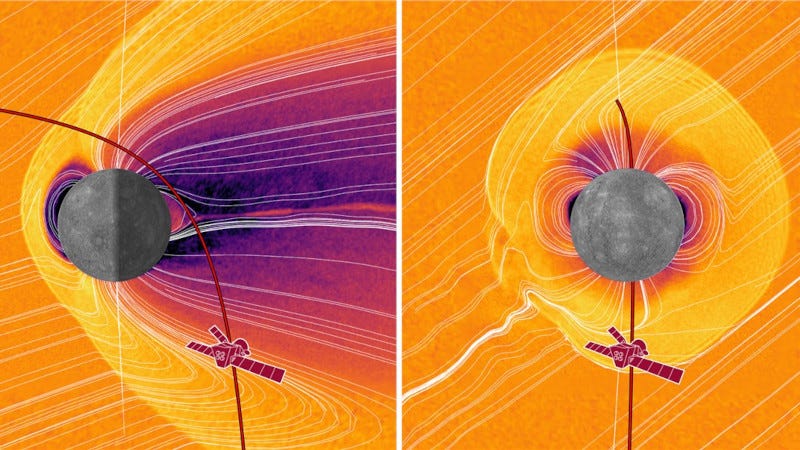

The ESA/JAXA BepiColombo mission soared just 183 miles above Mercury's surface this morning, with the closest approach happening at 06:59 CET (05:59 UTC/02:00 EST). This opportunity allowed the spacecraft to photograph Mercury, make unique measurements of the planet’s environment, and fine-tune science instrument operations before the main mission begin…